Did You Know? The Invention and Transfusion of Printing Technology in East Asia and its Implications for Knowledge Transfer

© Arian ZwegersPrior to the invention of any form of printing, creating texts was a highly time consuming and labour intensive process in which texts had to be copied out by hand from an original manuscript. This lengthy copying process meant that texts of all kinds were expensive to produce and relatively rare. This in turn kept the knowledge contained within them available to only an exceedingly small elite. With the invention first of woodblock printing, and later of moveable type printing, texts could be more affordably produced (although they remained a relatively rare and precious commodity) easing the development of large collections of works such as libraries. Although Gutenberg’s printing press, invented around 1440 CE in Europe, is generally considered to have sparked the ‘printing revolution’, the popularity of woodblock printing onto paper in China which began several centuries earlier and spread across East Asia constituted an important technological innovation in its own right. Whilst the invention of the printing press in Europe many centuries later did not utilise East Asia style printing technology directly, it may have been inspired by written and verbal accounts of Chinese printing technology which circulated in the Middle East and Europe at the time. Regardless, the spread of this early woodblock printing technology coincided with, and was advance by, another diffusion along the Silk Roads, that of Buddhism and in particular the demand for reproduced Buddhist texts and art.

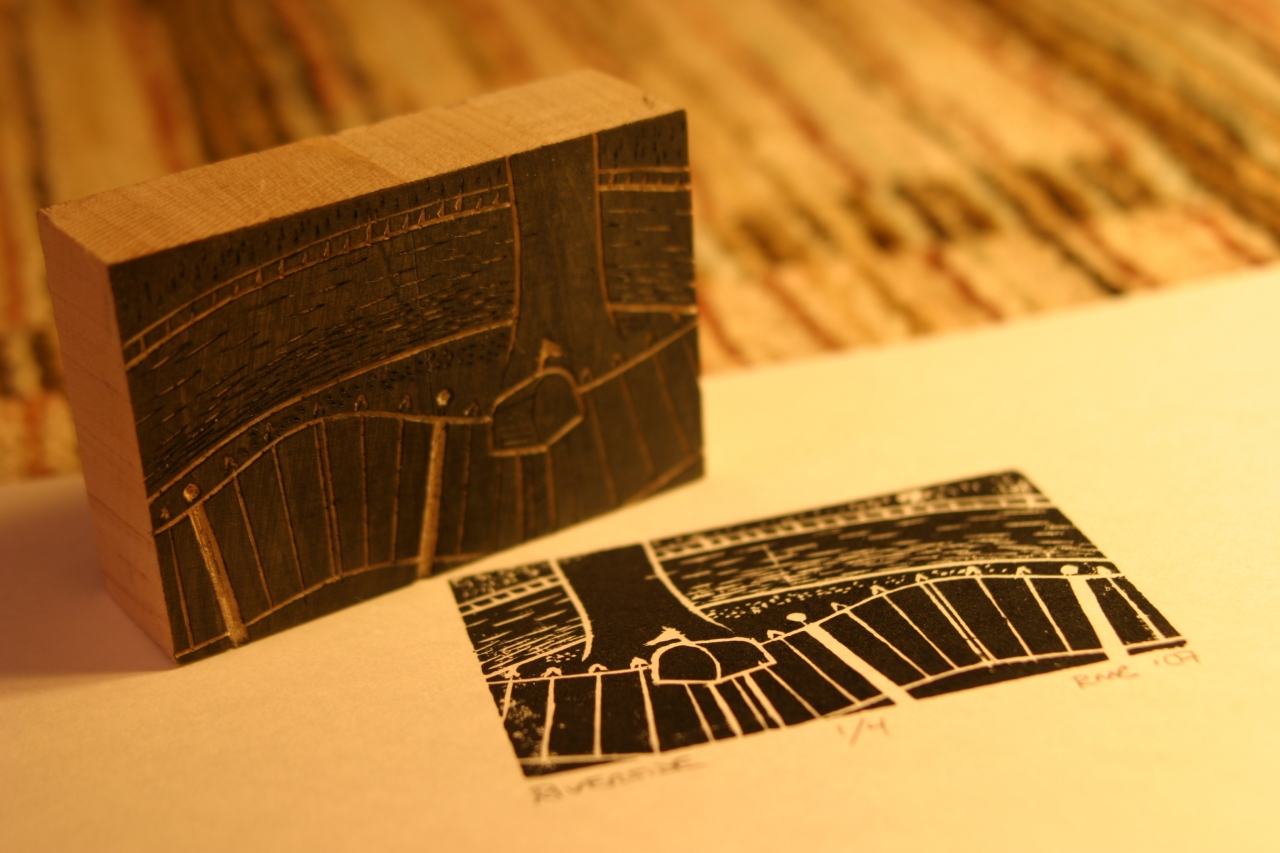

The printing of images onto silk and other fabrics using wooden blocks began in China some time before 220 CE. Later, in the 7th or 8th century CE the printing of text and images onto paper began to take place. In woodblock printing, text, images, or patterns are printed onto textiles or paper, using a wooden block covered in ink and onto which the intended pattern has been carved in the mirror image, this wooden block can then be reused to create as many copies of the same text as required. As it was far superior, cheaper, and more portable than the rolls of silk which had previously been used for writing, paper soon became the material of choice for writing and then printing onto. Wood block printing during this time was primarily used to produce religious texts and art. Indeed, the early rise of woodblock printing was heavily influenced by the spread of Mahayana Buddhism which placed a high value on texts and the ability to copy and therefore preserve them was considered an inherently virtuous activity. As such, the advantages of printing were quickly promoted by Buddhists who used woodblock printing to create ritual items, not intended for popular consumption but which would instead be ritually buried. Outside of a religious context, other popularly printed texts of time included the works of Confucius, dictionaries, and books on mathematics. Woodblock printing was quickly adopted in neighbouring societies to the northwest, and in Japan, and the Korean Peninsula to the east.

Following this, in the 11th century CE, another major innovation in printing, ‘moveable type’, was introduced, which, combined with an availability of relatively inexpensive paper, facilitated a boom in printed books which became more widely available in China during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279 CE). Instead of having one unique carved wooden block for each text, moveable type worked by having each individual alphanumeric character carved in relief, usually onto fired clay, which could then be fastened onto a plate, usually made from iron, in the desired order, removed and then re-ordered into different places on the plate to create a new text. These two different types of printing co-existed for centuries in China, although due to the large number of different characters in the Chinese written language and the complex ways in which they could be ordered, this printing technique did not have a dramatic impact in China at the time and woodblock printing remained popular. However, moveable type technology did quickly spread to the Korean Peninsula, where it was in frequent use by the 13th century. Moreover, the introduction of movable type also had implications for mercantile interactions as printing technology of this kind allowed for long numeric identifying codes to be easily printed onto paper money. The first paper money with identifying code printed onto it dates from 1161 CE, a practice remains in use to the present day.

Although this early printing technology did not necessarily diffuse in a linear manner in which a method of printing spread ‘wholesale’ from one region to another, there are a number of parallels between woodblock and moveable type printing in the East and the printing press revolution in Europe. For example, neither would have been possible without the invention and rapid spread of paper making technology along the Silk Roads. In addition, both were linked to a demand for more readily available religious texts, those of Buddhism in the case of woodblock printing and Christianity in response to Gutenberg’s printing press. Furthermore, there are some indications that the development of the printing press in Europe may have been influenced by various sporadic accounts of moveable type technology carried back to the region by returning merchants and missionaries from China. Regardless, the example of the spread and evolution of printing technology helps to contextualize the Silk Roads as routes of technological exchange and idea transfer in addition to that of mercantile activity.